By: Ahmad Mawlana and Fadi Zatari

Studies and Policy Papers/ April 2025

Abstract:

The paramilitary forces known as the “Gendarmerie” emerged as a novel mechanism for societal control following the French Revolution. In Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser instituted the Central Security Forces (CSF) in 1969, drawing inspiration from the French Gendarmerie model, in response to mass protests. However, he developed it to suit the security needs in Egypt, where its operation expanded to include both urban and rural areas, not just rural areas as in France and Türkiye. After President Nasser’s unexpected death in 1970, his deputy, Anwar Sadat, assumed power. During his tenure, the CSF underwent two significant developments. After the assassination of former President Sadat in 1981, President Mubarak restructured the CSF and deployed it across Egypt to ensure the regime’s ability to confront any local threats that might endanger it. Nevertheless, the CSF failed to quell the protests of January 2011 and collapsed, which contributed to Mubarak stepping down from his position. This article investigates the role of the CSF in sustaining Egypt’s authoritarian regimes from 1969 until the 2011 up- rising. It delves into the key internal and external factors behind the CSF’s formation and evolution while also analyzing the crucial circumstances that affected the forces’ performance during the 2011 revolution.

Keywords: Egypt, Central Security Forces, Paramilitary Forces, Gendarmerie, Security Studies

Table of Contents:

Introduction

- Theoretical Framework: Institutional Realism

- The Significance of the Study

- The Establishment of the CSF during Nasser’s Era

- The Rise of the CSF during Sadat’s Era

- Implications of the Bread Riots

- The Role of the CSF in Mubarak’s Era

- The CSF and Confrontation with Jama’a al-Islāmīyah

- The Road to the January Uprising

Conclusion

Introduction:

With the spread of gendarmerie forces, there has been growing interest in studying them within the theoretical and conceptual framework focused on the state. This interest includes examining how the state enforces new forms of discipline within society in response to economic and social unrest, as well as assessing the impact of internal security structures on the continuity or downfall of government authority.

The paramilitary forces known as “Gendarmerie” emerged as a new form of societal control after the outbreak of the French Revolution. It served as a tool to expand the state’s bureaucratic control and strengthen its hegemony, partic- ularly in rural and remote areas, and to address disturbances without the need to deploy the military locally, thereby reducing the risk of military coups. Addi- tionally, there were economic benefits related to the limited financial resources required to recruit an effective paramilitary force compared to professional mil- itary forces.1 The gendarmerie has emerged as an intermediary model bridging the gap between professional armed forces equipped with heavy weaponry and the police, serving as a civilian security apparatus. It was established as a nim- ble, well-armed security force possessing military capabilities without being di- rectly affiliated with the armed forces. However, its members received military training, lived in barracks, and were subjected to military jurisdiction.2

During the popular revolutions in Europe in the first half of the 19th century, many European countries, such as Italy and Spain, adopted the gendarmerie model from France. It was seen as a tool to prevent economic and social dis- turbances.3 In the post-colonial era, the model of paramilitary forces diffused from Europe to African and Asian states. The newly independent rulers faced significant challenges in maintaining their regimes. They turned to establish- ing security forces characterized by agility and strong armament, which served as the first line of defense for their regimes. One notable example is the Central Security Forces (CSF) established by President Gamal Abdel Nasser (1954- 1970) in Egypt in 1969, which was modeled after the French Gendarmerie and specialized in confronting local disturbances in Cairo and Alexandria.4 During President Anwar Sadat’s era (1970-1981), the CSF expanded signifi- cantly and assumed a pivotal role in upholding internal security, contributing to the support of authoritarian governance under President Hosni Mubarak (1981-2011). However, as indicated in this article, the CSF demonstrated in- efficacy when confronted by demonstrators during the January 2011 uprising.

Theoretical Framework: Institutional Realism:

Grafstein argues in his exploration of “institutional realism” that institutions are material entities whose existence depends on the behaviors within them rather than on beliefs about them. He critiques the reliance on rational actor theory to explain institutional behavior, suggesting instead that individuals’ responses shape the institutional constraints that govern others’ participation in the game. Grafstein’s thesis underscores the power struggles among state institutions, arguing that the state should not be viewed as a unified or cohesive entity, but rather as a collection of institutions, each with its agenda to advance its self-interest.

This article will draw on Hazem Qandil’s application of institu- tional realism to Egyptian state institutions, which posits that the Egyptian state is dynamic and that the ruling Egyptian elites are not a monolithic entity but a network of institutions, with the presidency, military, and security agen- cies at its core.6 Each of these institutions has its interests that occasionally align and at other times diverge.

This theoretical framework contributes to expanding our knowledge of how and when disputes within the policies of authoritarian regimes lead to the split of actors from ruling regimes. This framework helps to analyze why the Egyp- tian army stood by President Mubarak in the face of the 1986 revolt of the CSF. It also explains why the CSF failed to maintain Mubarak’s regime in 2011, given the conflicting interests between security agencies and the army’s pref- erence to preserve the leader’s interests, which the CSF saw as a risk if it tied its fate to Mubarak’s. This was especially true in light of the element of surprise of the unexpected demonstrations, in addition to the pressure exerted by the United States on the army to avoid killing protesters.7

The Significance of the Study:

It is to be noted that while numerous studies have explored the gendarmerie and paramilitary forces in France, Italy, Spain, and other European states,8 there is a lack of research on Egypt’s CSF. Analysis of the CSF’s role in Egypt contributes to understanding one of the most vital instruments of the Egyptian regime’s authority over society. This article aims to contribute to bridging the gap in the literature on civil-military relations, which tends to focus solely on military professionalism, intervention in politics, and coup prevention strate- gies while overlooking the authoritarian model that depends on civilian security forces.

This article encountered several hurdles, notably a lack of scientific literature on Egyptian security ap- paratuses and a scarcity of writings exclusively dedicated to the CSF. To navigate these challenges, the analysis gathered fragmented infor- mation from available official doc- uments and court papers spanning the period from the January 2011 revolution to the July 2013 coup. Notably, the analysis drew from the report of the Fact-Finding Commis- sion on the events of the January Revolution, established by President Mohamed Morsi through a presidential decree. Additionally, the article relied on interviews published in newspapers and websites featuring numerous CSF leaders during the research period, enabling the collection of various pieces of information to construct a more comprehensive understanding of the CSF.

The Establishment of the CSF during Nasser’s Era:

In 1967, the Egyptian military suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of the Israeli military.9 The attack revealed that the aviation command had ignored intelligence warnings of an imminent Israeli attack on Egyptian airports and left the aircraft without shelters or fortifications. Nasser was afraid of internal reactions against him after the 1967 defeat and told his assistants, “The stability of the domestic front will not last long, and citizens will not tolerate the shock for more than six to nine months.”10

The defeat of 1967 represented a blow to the state media, which broadcasted false news about the Egyptian military’s victory during the early days of the war. Consequently, the youth began to question the reasons behind the disas- trous defeat and citizens’ confidence in the Nasser regime was shaken. It was reflected in public protests on the streets in February 1968 for the first time since the military coup in 1952.11 The protests commenced with the demon- stration by workers from the military factories in the Helwan neighborhood on February 21, 1968. They protested against the perceived lenient sentences handed to Air Force leaders accused of military negligence during the war. Clashes occurred between the protesters and the police forces in front of the Helwan police station. As news spread of the police repression of the workers in Helwan, university students in Cairo and Alexandria began to demonstrate, they marched out of their universities into the streets. Clashes continued until February 27, resulting in the death of two workers, injuries to 77 workers and students, and the arrest of 635 people.12

The student and labor protests did not aim for the overthrow of Nasser’s re- gime; instead, they advocated for policy improvements and internal reforms within the existing regime. As a result, Nasser did not respond to these protests with violent repression. To quell the anger in the streets, Nasser issued an offi- cial statement known as the March 30 Declaration, in which Nasser pledged to keep the military out of politics and to establish a new political system through a new constitution. Nasser also decided to retry the officers accused of negli- gence in the war.13

The streets had barely calmed down before another student protest erupted on November 20, 1968, objecting to amendments to the education law that in- cluded raising the minimum required grade for passing courses. The demon- strations began this time in the city of Mansoura, where four protesters were killed including three students, and 32 others were injured.14 News of the pro- tests spread, sparking widespread demonstrations at Alexandria University and in the city streets in response to the killing of protesters in Mansoura. The protests in Alexandria resulted in the death of 16 people, including three stu- dents, and 167 others were injured.15

The police forces were unable to suppress the protests, and the governor of Alexandria and former military officer, Ahmed Kamel, attempted to negotiate with the protesting students. However, Kamel failed to convince them to end the sit-in at the university and halt the protests. Kamel then requested mili- tary intervention from Nasser, who agreed.16 Kamel requested the commander of the northern military region, encompassing Alexandria, to deploy military helicopters over the sit-in locations, implying that force might be employed to disperse the gatherings. Subsequently, military tanks were positioned in front of the university and the governorate building, prompting the students to en- gage with Kamel and communicate their decision to conclude the sit-in and cease the protests.

The student protests were not solely a reaction to the diminished military sen- tences for Air Force chiefs but rather a response to the circumstances that led to the 1967 defeat. Consequently, Nasser started contemplating the establish- ment of a new security apparatus capable of quelling anticipated protests with- out solely depending on the military. The leader aimed to rebuild and redirect the military’s focus toward its primary mission of defending Egypt’s borders and liberating Sinai from Israeli occupation. This consideration arose from the failure of the police forces, designated as the “security forces,” to effectively address the demonstrations.

The Nasserist regime established a lightly armed and well-equipped police force specialized in confronting local disturbances. After the accomplishment of the training, a ministerial decision was issued in August 1969 to establish the CSF under the name of the Central Reserve of the Ministry of Interior. The number of forces reached 189 officers and 11,690 soldiers under the supervi- sion of the Assistant Minister for Training and Personnel Affairs,17 and the CSF was stationed in Cairo and Alexandria.18

The former Head of General Investigations, General Hassan Talaat, credited the proposal for the establishment of the CSF to himself. During a 12-day trip to Paris in May 1967 to visit French law enforcement agencies, Talaat stated that the idea of establishing the CSF in its current form came to mind after ob- serving two French security teams. One of them was called the CRS, short for “Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité,” while the other was the Gendarmerie, a military unit that works in police work during peacetime under the Ministry of Interior and is subject to the Minister of War’s orders during wartime.19 Although Hassan Talaat’s visit to Paris occurred in 1967, two years prior to the establishment of the CSF, the concept of its formation might have crystal- lized in his mind during this visit. This idea later gained traction within the political leadership and transitioned into the implementation phase following the student protests in 1968. Nasser’s regime adopted the gendarmerie model from France. However, it tailored the forces to suit local circumstances by in- tegrating them into the Ministry of Interior rather than placing them under the military’s control. As a result, the forces were deployed to operate in the capital Cairo and the city of Alex- andria, which witnessed unrest, in- stead of solely focusing on rural ar- eas as was the case in France. Nasser passed away in 1970 before witness- ing the CSF’s deployment in quelling protests.

The Rise of the CSF during Sadat’s Era:

According to institutional realism theory, it can be argued that there was a competition between Sadat and the military. Sadat, who served as an officer in the Signal Corps and had no influence in the ground forces, began his rule by shifting control over internal affairs away from the military’s grip. This was a policy that Nasser had already begun after the 1967 defeat but at a slower pace compared to the advanced steps taken by Sadat. In 1971, Sadat adjusted the police law, whereby the Minister of the Interior must be a police officer.

Law No. 109 of 1971 regulating the police institution played with words in its definition of the police force in Article 1 as a “civilized regular” force, despite its members holding military ranks and some of its components being equipped with heavy weapons, including armored vehicles, and stationed within bar- racks. The term “regular” was used to justify the militarization of the police force by considering the recruitment of young people into the police as part of the national service.20 The CSF soldiers are recruited from citizens required for military service. Exempted from service in the police force are graduates of universities and higher institutes in Egypt or their foreign equivalents, holders of secondary or equivalent certificates from abroad, and those who have mem- orized the entire Quran.21 According to these criteria, the police force tends to recruit the most illiterate individuals who are more accepting of orders with- out discussion and have less awareness of human rights and political contexts of events.

Sadat considered the CSF as the second line of defense for the internal front. He relied on it to secure cities along the Suez Canal as a rapid response force for vital targets in case of danger and to secure the entrances of Cairo against any attempts of Israeli aerial infiltration. Following the success of the Egyptian military in crossing the Suez Canal during the October 1973 War and Pres- ident Sadat’s initiation of direct negotiations with the Israelis under American sponsorship, the need for the CSF in the canal area receded. In 1974, Sadat issued Republic Decision No. 595. It called for the establishment of a general administration within the Ministry of Interior, named the “General Administration for Central Re- serve Forces,” with the responsibility of maintaining security against any breach or disturbance and assisting police forces in security directorates.22 Brigadier General Mohammed al-Hadidi was appointed as the Director of the General Administration for Central Reserve Forces.23 Then, in 1976, a Republican decision was issued to promote Brigadier General al-Had- idi to the rank of assistant minister of interior, making him the first central reserve commander to hold such a position.24 This rank is the second highest position in the Ministry of Interior after the minister, indicating the impor- tance of the CSF within the security apparatus.

Implications of the Bread Riots:

The masses could not bear the government’s announcement of increasing prices of 25 essential commodities, including bread, sugar, and fuel, in Jan- uary 1977, by percentages ranging from 20 to 30 percent, in response to the demands of the International Monetary Fund to reduce government subsidies provided to citizens.25

Massive protests and violent incidents erupted on January 18-19, 1977 in Cairo and Alexandria, swiftly extending to encompass nine governorates. These events posed a significant challenge, prompting the head of the State Security Investigations Service (SSIS), Major General Hassan Abu Basha, to express in his memoirs that: “There was no doubt at that moment that the situation was rapidly evolving into a comprehensive popular revolution.”26 Sadat named al-Gamasy as the military’s leader and ordered him to control the situation and maintain order in the streets.27 Al-Gamasy demanded the cancellation of government decisions to reduce subsidies and increase prices as a condition for the military’s intervention. So, the Cabinet canceled the decision to raise prices on January 19, the day on which the military was de- ployed in the streets.

The geographical spread of the demonstrations exceeded the capabilities of the CSF to contain them, and there was a shortage in the number of CSF forces allocated to confront the riots.28 President Sadat ordered the reorganization of the CSF to ensure its ability to confront potential public protests and extended the CSF’s presence beyond Cairo, Alexandria, and the Suez Canal regions by creating the Assiut Security Zone centered in the city of Assiut and the Central Delta Security Zone centered in Tanta.29 The number of CSF recruits increased to 110,000, an unprecedented increase that transformed the CSF into a mili- tary controlled by the Ministry of Interior.30 This surge had a critical impact on the allocation of significant resources that burdened the country, including the establishment of a vast infrastructure of camps, logistics, nutrition, armament, and training.

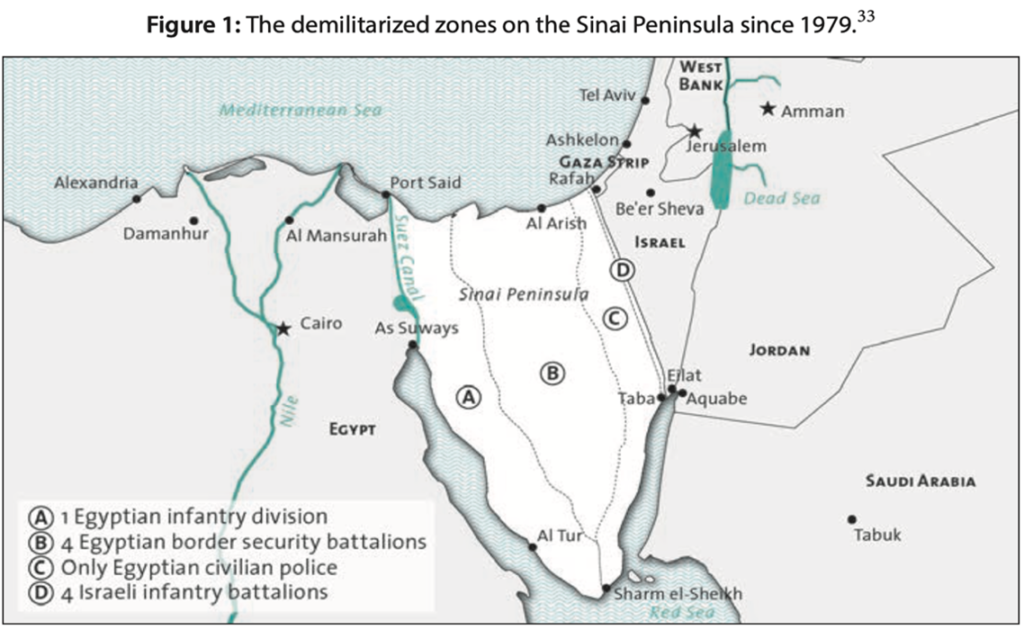

Later Egypt and Israel were assigned a peace agreement in 1979. The treaty stipulated that the Egyptian police would be armed with light weapons and perform regular police duties within Area “C,” extending from Rafah to Taba (Figure 1).31 In the desert environment that characterizes the border area, which spans 277 kilometers, only the CSF was suitable for deployment. As a result, the political and security significance of the CSF increased through its assignment with the task of securing the Egyptian borders with Israel and the Gaza Strip. For the first time, the CSF was armed with heavy weapons, includ No. 168, February 2015 ing armored vehicles and small helicopters,32 instead of its previous armament with only automatic rifles and batons.

The Role of the CSF in Mubarak’s Era:

After the assassination of Sadat in 1981, Hosni Mubarak assumed the presidency and remained in this position for 30 years (1981–2011). In the context of enhancing police strength, Mubarak made several changes to the organizational structure of the CSF. In 1985, a presidential decree was issued to cre- ate two new general administrations in the Suez Canal and Sinai regions and Upper Egypt.34 With this, the general administrations of the CSF covered all of Egypt, ensuring that the regime could confront any internal threats to the country’s security.

A separate department was established for “special operations,” which fo- cused on executing combat operations, guarding significant facilities such as embassies, airports, and radio and television stations, and supporting police operations in the desert and mountainous areas. Each camp of the CSF in- cluded several battalions, with each CSF battalion consisting of three com- panies.35 The number of soldiers in a single CSF company ranged from 250 to 360, while the number of officers ranged from 11 to 16. The CSF conscrip- tion period is three years. Additionally, the CSF undertook various tasks, including suppressing student protests in universities, intimidating striking workers in factories, and farmers protesting the poor supply of irrigation water.36

By 1986, Egypt was suffering from a crisis in paying off its debts, which had reached $25 billion.37 At that time, the exchange rate of the U.S. dollar had reached 70 piasters.38 In December 1985, the low monthly salaries of CSF soldiers, which amounted to 6 pounds, were reduced by 80 piasters over five months under the pretext of contributing to paying off Egypt’s debts.39

The spark of the CSF rebellion was ignited on February 24, 1986, following a letter from the Recruitment Department at the Ministry of Interior to the Giza Security Forces Camp. The letter requested that the camp administration post- pone sending the files of those soldiers who may serve for an additional year until further instructions were issued. The soldiers interpreted the decision as their conscription would be extended for a fourth year.40 The members of the camp began a rebellion on the evening of February 25. The soldiers burned their barracks and proceeded to the surrounding streets, where they set fire to and destroyed nine hotels, 42 casinos, and nightclubs.41 As the rebellion spread, the Minister of Interior advocated for the deployment of the military to regain control of the situation. He hesitated to dispatch additional units from the CSF to suppress the rebellion out of concern that these units might potentially align with the rebels.42

On February 26, the military deployed brigades from the Special Forces and armored divisions to the capital and imposed a curfew in Cairo and the sur- rounding urban areas of Giza and Qalyubia.43 The military’s objective was to regain control over the rebellious CSF camps, which saw fierce confrontations that ended on February 27. The Ministry of the Interior later announced the official tally of casualties, which totaled 107 fatalities and 719 injured.44 The Minister of Interior revealed that the number of participants in the rebellion was 17,000 soldiers.45 On March 6, 1986, Zaki Badr, the new Minister of Interior, revealed that the number of CSF personnel was 106,000 soldiers and 3,114 officers distributed across 41 camps.46

Despite the CSF’s rebellion, Mubarak did not de- cide to dismantle or get rid of the forces due to their importance in suppressing public protests and con- fronting Islamic groups that were spreading at the time. Therefore, the decision was issued to transfer many of its camps to areas further from Cairo while improving the living conditions for soldiers in the barracks.

The CSF and Confrontation with Jama’a al-Islāmīyah:

The Jama’a al-Islāmīyah Group, which was involved in the assassination of President Sadat in 1981, believed that one of the primary reasons for the failure of their plan to overthrow the government was the lack of sufficient popular support to ignite a revolution. Consequently, the group decided to postpone their confrontation with the government for a few years until they could build a larger base of popular support. In the meantime, they began to establish a military wing to protect the group from repression by the security forces.47

With the appointment of Zaki Badr as Minister of Interior following the CSF rebellion in 1986, Badr adopted the slogan “Striking at the Heart” against members of the Islamic groups. The CSF, acting primarily on the directives of the State Security Investigations Service (SSIS), implemented this approach. In retaliation, members of the Jama’a al-Islāmīyah attempted to assassinate Zaki Badr in 1989 using a car bomb, which did not detonate. During this period, Egypt entered a phase of intense conflict. According to the Ministry of Interior, the Jama’a al-Islāmīyah carried out approximately 1,314 attacks between 1992 and 1997. These attacks resulted in the deaths of 471 members of the group and the arrest of around 20,000 of its members.48

Under the intense security crackdown by the CSF, the Jama’a al Islāmīyah reached an impasse. On July 5, 1997, its leaders announced an unilateral cease- fire. This ceasefire was followed in 2002 by a series of books published by the group’s leaders in which they renounced their previous ideologies.49 This step marked the end of the era of confrontations between the Islamic group and the security forces. The CSF played a crucial role as the military arm of the Ministry of Interior, while the SSIS handled the strategic planning and execution of counterterrorism measures.

The Road to the January Uprising:

Since Mubarak opened the way for par- liamentary elections in 1984, he has relied on the police to rig the election results in favor of the ruling party.50 This approach was achieved through repression and coercion by the CSF against opposition candidates and their supporters.51 At the turn of the mil- lennium, the influence of the SSIS in-

creased in the local arena during the tenure of Interior Minister Habib al-Adly, who remained in his position for 14 years (1997-2011). The SSIS dominated political life, and the number of arbitrary arrests increased to include thou- sands of citizens. Police brutality against citizens became widespread, and the relationship between the police and citizens deteriorated to the point where it resembled that of a master and slave. The press became increasingly restricted, prompting the organization Reporters without Borders to rank Egypt 127th out of 178 countries in the 2010 Press Freedom Index.52

In 2010, several events acted as the straw that broke the camel’s back, igniting the spark that led to the January uprising. Among the most notable events was widespread election fraud during the parliamentary elections, so the ruling party won 97 percent of the parliamentary seats, and 49 police officers were elected as members of parliament.53 It became widely believed that Egypt had transformed during Mubarak’s era from a military state into a police state.

Then came the incident of the killing of the young man Khaled Saeed at the hands of police in the summer of 2010. Pictures of his body with signs of bru- tal beating spread. Some young people created a Facebook page called “We are all Khaled Saeed,” which attracted more than half a million followers in three months. Egyptians felt that no one was safe anymore,54 and the page called for citizens to demonstrate on January 25, the celebration of Police Day. This call came in conjunction with the revolutionary atmosphere in Tunisia, which led to the overthrow of President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali in early 2011.

Mubarak underestimated the growing wave of public anger against him, as he succeeded in holding onto power for 30 years, facing little organized opposi- tion except for the Muslim Brotherhood, which was not seeking a revolution in Egypt. Interior Minister Habib al-Adly said in an interview on January 25, “Those who plan to take to the streets have no weight … Security forces are capable of deterring them … and those who hope to repeat the Tunisian sce- nario are teenagers.”55

The surprise came on January 25 when several thousand protesters responded to calls to demonstrate in Cairo and other cities such as Suez, Mahalla, and Damietta. The CSF resorted to using rubber bullets, tear gas, and water can- nons to disperse the protesters, and around 4,000 demonstrators were ar- rested.56 However, the protests continued over the next two days and calls for extensive demonstrations spread following Friday prayers on January 28.

The protests continued, and the military issued several statements acknowl- edging the protesters’ demands and refusing to use force against them. In the end, the efforts of the CSF and the ruling regime to suppress the uprising were unsuccessful as the protests and demonstrations became more massive and widespread, leading Mubarak to announce his resignation on February 11 after 18 days of continuous protests. The military prioritized its institutional interests over President Mubarak’s stay in power, allowing the collapse of the CSF and the entire police force. This pressure led Mubarak to step down amid the siege of his presidential palace in Cairo by protesters, while the army en- sured Mubarak’s safe exit from power.

According to the former head of the SSIS, General Hassan Abdel Rahman, the estimates of the SSIS anticipated the participation of 5,000 protesters in the January 28 demonstrations in Cairo.57 Based on that, a plan was drawn up to confront the protesters with 17,000 CSF soldiers in Cairo.58 However, the Ministry of Interior was surprised by the massive participation of protest- ers, numbering hundreds of thousands in Cairo.59 Furthermore, the protests persisted for several consecutive days, resulting in exhaustion among the CSF forces. They faced depleted ammunition and fatigue due to continuous work without rest. This led to the exhaustion of wireless device batteries coinciding with disruptions in phone networks, impeding communication between sol- diers and their leaders. Consequently, with support severed from the troops, the field formations withdrew from their positions.

The reasons for the failure of the CSF to suppress the January protests can be summarized as follows: Political deadlock, deteriorating economic conditions, widespread human rights violations, increased poverty and unemployment caused by Mubarak’s policies over 30 years, and the growing talk of his son, Gamal, inheriting power, prompted huge numbers of citizens to respond to calls to protest. The Ministry of the Interior failed to comprehend the extent of public anger and provide estimates anticipating limited protests for one day, while large numbers of protesters took to the streets in a wide geographical

area for several consecutive days, exhausted the CSF and contributed to cut- ting off their supply lines, causing their soldiers to withdraw haphazardly from the streets, especially in Cairo. This chaos and confusion led to a breakdown in communication between the leadership of the Ministry of Interior and the troops on the ground.

The participation of diverse sectors of citizens in the protests hindered the CSF from engaging in widespread killings of protesters, given the negative reper- cussions that would have fueled the protests. Moreover, the lack of a specific organizational structure for the protest organizers impeded the ability of the SSIS to arrest individuals who could have ended the protests via detainment. The military’s decision to withdraw support for Mubarak and refrain from backing the Central Security Forces (CSF) under mounting public pressure reflected concerns over potential defections within its ranks if it moved against the people. This shift was further reinforced by U.S. President Obama’s explicit call for Mubarak to step down and avoid suppressing protesters.60

According to institutional realism, the Egyptian military’s alignment with Mubarak in 1986 during the CSF rebellion can be attributed to the perception that its institutional interests were not under immediate threat. Furthermore, the CSF rebellion offered a chance to reaffirm the military’s role as the guard- ian of the ruling regime. However, a contrasting situation unfolded during the 2011 protests when the military prioritized its institutional interests over those of Mubarak. In 2011, the military was concerned about the potential conse- quences of engaging in widespread repression against the protesters who had united against the ruling regime. Additionally, pressure from the United States to persuade Mubarak to step down and prevent further suppression of the cit- izens heightened the military’s concerns and encouraged it to move away from Mubarak’s support.

After the July 2013 coup, Abdel Fattah el-Sissi learned a pivotal lesson from the collapse of the CSF in the face of the demonstrators during the January 2011 uprising. Therefore, in March 2014, he established rapid intervention forces from all branches of the armed forces, with a strength equivalent to two mili- tary divisions, to participate in confronting the demonstrations, especially in Cairo and Alexandria.61 The CSF remained to act as a strike force for the Min- istry of Interior.

Conclusion:

The defeat of the Egyptian military in the 1967 war led to Nasser reducing the military’s role in internal affairs, distancing it from politics, and focusing on rebuilding the military based on professional competence. Despite this effort, Nasser faced angry public protests over policies that led to their defeat. Protests began in February 1968 by students and workers following lenient prison sentences for Air Force leaders accused of negligence in the 1967 war. Security forces could not confront the protests that repeated in November 1968, forcing Nasser to rely on the military to disperse student sit-ins and public protests. Nasser began thinking about building a new security apparatus capable of suppressing mass demonstrations, leading to the militarization of the police in Egypt since the establishment of the CSF in 1969, which became the first line of the regime’s defense against mass protests.

This article concluded that the CSF failed to respond to massive, unexpected public protests, as happened in January 1977, leading Sadat to rely on the military to suppress the unrest. Similarly, during the January 2011 protests, Mubarak turned to the military for support, but the latter prioritized its insti- tutional interests over those of Mubarak, refusing to side with him.

The repressive tactics employed by the CSF to uphold regime security gener- ated fear and hatred among citizens, ultimately undermining the legitimacy of the police force and the state itself. As a result, public protests are more likely to occur, prompting the head of state to rely on the military for support. This situation, in turn, carries the inherent risk of a military coup, as was witnessed during the January 2011 revolution under Mubarak’s regime.

Reforming the CSF requires a broader framework that focuses on the indi- vidual as a reference for security concepts, rather than the state or the ruling regime. This shift would propel the adoption of sound policies aimed at pro- tecting citizens from tyranny and granting them the freedom to choose their rulers, as well as the power to hold them accountable through political and constitutional channels. Such an approach would reduce the need for massive security apparatuses dedicated to suppressing the masses and open the door to embracing modern policing models that uphold the dignity of citizens, such as community policing. Additionally, it would alleviate the burden of exorbi- tant economic expenses associated with recruiting and sustaining hundreds of thousands of CSF forces.

Practical measures that can contribute to reforming the CSF include: changing the CSF military culture by abolishing regulations that enforce military hierar- chy within its ranks and appointing a civilian director to lead it; reducing the percentage of illiterate individuals among the CSF personnel; ensuring trans- parency and accountability by publicly disclosing the CSF’s annual budget and subjecting its activities to oversight by the parliament and society; Granting the CSF the responsibility of rapid intervention and riot control, accompanied by clear regulations that outline the proper use of force and the consequences of violating these regulations; establishing a system for voluntary recruitment and affiliation to the CSF and eliminating the mandatory assignment of re- cruits to join. Implementation of these measures will not only alleviate the tension between the ruling regime and society but also enhance the legitimacy of the state and diminish the reliance on huge security apparatuses.

This paper was originally published by: Insight Turkey Journal 2025 . Vol. 27 / No. 1 / pp. 217-234.

Endnotes:

1. Morris Janowitz, Military Institutions and Coercion in Developing Nations, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977), p. 48.

- Radley Balko, Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces, (New York: Public Affairs, 2013), p. 24.

- Derek Lutterbeck, “Between Police and Military: The New Security Agenda and the Rise of Gendar- meries,” Cooperation and Conflict: Journal of the Nordic International Studies Association, Vol. 39, No. 1 (March 2004), p. 49.

- Hassan Talaat, Fi Khidmat Al’amn Alsiyasii: May 1939 – May 1971 [In the Service of Political Security: May 1939 – May 1971], (Beirut: al-Waṭan al-ʻArabī lil-Tawzīʻ wa-al-Nashr, 1983), p. 144.

- Robert Grafstein, Institutional Realism: Social and Political Constraints on Rational Actors, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

- Hazem Kandil, Soldiers, Spies and Statesmen: Egypt’s Road to Revolt, (London: Verso, 2012).

- Ben Rhodes, The World as It Is: A Memoir of the Obama White House, (New York:, Random House Publishing Group, 2018), pp. 112-115.

- J. L. Hovens and Gemma van Elk (eds.), Gendarmeries and the Security Challenges of the 21st Century, (Netherlands: Koninkijke Mare Chaussee, 2011), pp. 18-21.

- Kandil, Soldiers, Spies and Statesmen: Egypt’s Road to Revolt, p. 102.

10. Ahmed Abdalla, The Student Movement and National Politics in Egypt, 1923-1973, (London: Al Saqi Books, 1985), pp. 146-151. - Abdalla, The Student Movement and National Politics in Egypt, pp. 150-151.

- Mohamed Abd al-Salam, Sanawāt ʻaṣībah: Dhikrayāt nāʼib ʻām [Rough Years: Memories of a Public Sec- tor], (Cairo: Al Shorouk House, 1975), pp. 121-123.

- Al-Salam, Sanawāt ʻaṣībah: Dhikrayāt nāʼib ʻām, p. 158.

- Abdalla, The Student Movement and National Politics in Egypt, p. 164.

- Abdalla, The Student Movement and National Politics in Egypt, p. 158.

- Ahmed Ezz al-Din, Ahmed Kamel Yatadhakkar: Min ‘awraq rayiys almukhabarat alama [Ahmed Kamel Remembers: From the Papers of the Former Egyptian Intelligence Chief ], (Cairo: Dar Al-Hilal, 1990), p. 100.

- Mohamed el-Jawadi, Qiyādāt al-Shurṭah fī al-siyāsah al-Miṣrī: 1952-2000 [Police Leaders in Egyptian Politics: 1952-2000], (Cairo: al-Hayʼah al-Miṣrīyah al-ʻĀmmah lil-Kitāb, 2008), p. 71.

- Najla Zekry, “Mādhā yaqūlu al-rajul alladhī khiṭaṭ wa-fikr lʼdkhāl al-amn al-Markazī fī Dāʼirat al-ʻamal albwlysy fī Miṣr?” [What Does the Man Who Thought and Planned for Central Security to Enter the De- partment of Police Work in Egypt Say?], Al-Ahram, (March 6, 1986), p. 3.

- Talaat, Fi khidmat al›amn alsiyasii, p. 144.

- “Taqrir hayyat mufawadi aldawla,” State Commissioners Authority, (September 2014), p. 6.

- “Taqrir hayyat mufawadi aldawla,” State Commissioners Authority, p. 4.

- “Decree of the President of the Arab Republic of Egypt No. 595 of 1974,” The Egyptian Official Gazette, (May 2, 1974).

- “Decree of the President of the Arab Republic of Egypt No. 1323 of 1974,” The Egyptian Official Ga- zette, (August 29, 1974).

- “Decree of the President of the Arab Republic of Egypt No. 431 of 1976,” The Egyptian Official Gazette, (June 3 1976).

- Mohamed Hasanayn Haykal, Khurayyif al-ghaḍab: ightiyāl al-Sādāt [Autumn of Fury: The Assassination of Sadat], 1st ed., (Cairo: Al-Ahram Center, 1982), pp. 185-186.

- Hassan Abu Basha, Fī al-amn wa-al-siyāsah [In Security and Politics], (Cairo: Dar al-Hilal, 1990), p. 20.

- Abu Basha, Fī al-amn wa-al-siyāsah, p. 188.

- Abu Basha, Fī al-amn wa-al-siyāsah, p. 51.

- Zekry, “Mādhā yaqūlu al-rajul alladhī khiṭaṭ wa-fikr lʼdkhāl al-amn al-Markazī fī Dāʼirat al-ʻamal alb- wlysy fī Miṣr?”

- Zekry, “Mādhā yaqūlu al-rajul alladhī khiṭaṭ wa-fikr lʼdkhāl al-amn al-Markazī fī Dāʼirat al-ʻamal alb- wlysy fī Miṣr?”

- Mahmoud Fawzi, Asrār al-Muʻāhadah al-Miṣrīyah al-Isrāʼīlīyah [Secrets of the Egyptian-Israeli Treaty], (Cairo: Najdi for Publishing and Distribution, 1991), pp. 154-189.

- “Interview with Major General Hosni Ghanayem, Tragedy of the Central Security Soldier Begins on the Day of Jalalib,” Al-Wafd, (March 6, 1986), p. 6.

- “Sinai Peninsula from Buffer Zone to Battlefield,” Center for Security Studies, (February 2015).

- “Decree of the President of the Arab Republic of Egypt No. 331 of 1985,” The Egyptian Official Gazette,

(August 22, 1985).

- “Report of the Fact-Finding Committee on the events of the January Revolution,”Testimony of Major General Jalal Ali, Undersecretary of the General Administration of the Cairo CSF, Civilization Center for Research, Studies and Training , (2012), P:835-836.

- Robert Springborg, Mubarak’s Egypt Fragmentation of the Political Order, (Boulder, Colorado: West- view Press, 1989), pp. 142-143.

- “25 milyar dolar hajm duyun misr alkharijia [25 Billion Dollars, the Size of Egypt’s Foreign Debt],” Al-Ahram, (February 24, 1986).

- “Rayiys alwuzara’ yuakid: sier aldolar 70 qirshan eind aihtisab aldarayib aljumrukiat ealaa alwaridat [The Prime Minister Confirms: The Price of the Dollar Is 70 Piasters when Calculating Customs Taxes on Imports],” Al-Ahram, (February 25, 1986).

- Waheed Raafat, “Firaq al’amn almarkazii hal tabqaa am tuhl? [CSF: Will They Remain or Dissolve?],” Al-Wafd, (March 6, 1986).

- “Bayan alnaayib aleami ean ‘ahdath alshaghab [The Public Prosecutor’s Statement on the Riots],” Al-Ahram, (April 4, 1986).

- “Estiqrar almawqif al’amni wahasr khasayir al’ahdath al’akhira [The Stability of the Security Situation and Counting the Losses of the Recent Events],” Al-Ahram, (February 28, 1986).

- Kandil, Soldiers, Spies and Statesmen: Egypt’s Road to Revolt, p. 222.

43. “Tamarud junud al’amn almarkazii fatuaqif alzaman 67 saat [The CSF Soldiers Revolted, and Time

Stopped for 67 Hours],” Al-Wafd, (March 6, 1986).

- Nameless, “Abu-Ghazala Agrees to Immediately End the Recruitment of Unfit Elements in the Police,” Al-Ahram, (March 6, 1986), p. 1.

- Nameless,“Reconsidering the Locations of the Security Forces’ Camps to Move Them Outside the Cities,”, Al-Ahram, (March 4, 1986), P. 6.

- Nameless,“Abu-Ghazala Agrees to Immediately End the Recruitment of Unfit Elements in the Police,” Al-Ahram, (March 6, 1986), p. 1.

- Salwa Al-Awa, Jama’a al-Islāmīyah fi misr 1974-2004 [The Jama’a al-Islamiyya in Egypt: 1974-2004], (Cairo: Al-Shorouk International Library, 2006), pp. 110-114.

- Mohamed Hamza, Mukafahat alirihab waltataruf wa’uslub almurajaeat alfikri [Combating Terrorism and Extremism and the Method of Intellectual Review], (Cairo: Egyptian Ministry of Interior, 2012), p. 16.

- Najeh Ibrahim abd-Allah, Karam Muhammed Zuhdi, Ali Muhammad Ali al-Sharif, Nahr The River of Memories: Jurisprudential Reviews, (Cairo: Islamic Heritage Library, 2003), p. 35.

- Mohamed Hasanayn Haykal, Mubarak and His Era from the Platform to Tahrir Square, (Cairo: Al Shorouk, 2012), p. 121.

- Springborg, Mubarak’s Egypt Fragmentation of the Political Order, pp. 142-143.

52. “Press Freedom Index 2010,” Reporters without Borders, retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://rsf.org/

en/world-press-freedom-index-2010.

- Mohamed Muslim, “Al-Masry al-Youm Confronted Fathi Sorour with Accusations, So He Revealed Dangerous Secrets,” Al-Masry Al-Youm, (March 24, 2011), retrieved October 20, 2023, from https://www. akhbarway.com/elakhbar/news.asp?c=2&id=83570.

- Jose Antonio Vargas, “Spring Awakening,” The New York Times, (February 17, 2012), retrieved October 20, 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/19/books/review/how-an-egyptian-revolution-be- gan-on-facebook.html.

- Kandil, Soldiers, Spies and Statesmen: Egypt’s Road to Revolt, p. 290.

56. Sherif H. Kamel, “Egypt’s Ongoing Uprising and the Role of Social Media: Is There Development?,”

Information Technology for Development, Vol. 20, No. 1 (2014), p. 85.

- “Report of the Fact-Finding Committee on the Events of the January Revolution Testimony of Major General Hassan Abdul Rahman,” Undersecretary of the General Administration of the Cairo (CSF), Civiliza- tion Center for Research, Studies and Training , (2012), P.855

- “Report of the Fact-Finding Committee on the Events of the January Revolution Testimony of Major General Ashraf Hassan Rahman,” Undersecretary of the General Administration of the Cairo (CSF) Civiliza- tion Center for Research, Studies and Training , (2012), P. 458.

- Osama Khaled, “Qayid al’amn almarkazii bialqanat ean althawrati: ramzi manieana min astikhdam alsilah fahozmn” [Central Security Commander in the Canal Zone on the Revolution: Ramzy Prevented Us from Using Weapons, so We Were Defeated], Al-Masry Al-Youm, (March 15, 2011), retrieved October 20, 2023, from https://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/119278.

- Rhodes, The World as It Is: A Memoir of the Obama White House, pp. 112-115.

- Omar Al-Zawawi, “Qūwāt al-Sīsī lil-tadakhkhul al-Sarī: qūwat Umm istiʻrāḍ [Sisi’s Rapid Interven- tion Forces: Force or Show?],” Al Jazeera, (March 27, 2014), retrieved October 20, 2023, from: https:// www.aljazeera.net/news/2014/3/27/%D9%82%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84% D8%B3%D9%8A%D8%B3%D9%8A-%D9%84%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%AF%D8%AE%D9%84-%D8%A7 %D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%B9-%D9%82%D9%88%D8%A9-%D8%A3%D9%85.

Ahmad Mawlana

Ahmad Mawlana is a Master’s researcher in International Relations, he writes and publishes regularly with several research centers and lectures on the subject at various academic institutions. His publications include: “The Security Mindset in Dealing with Islamic Movements”, “Roots of Hostility”, “Numerous studies on Jihadi movements”, and “A study on Egypt’s Central Security Forces”.

Fadi Zatari

Fadi Zatari is an Assistant Professor of political science and international relations at Istanbul Sabahattin Zaim university. He was a lecturer in political science and IR from 2017 to 2021 at the same university. Dr. Zatari received his education in Palestine, Germany, and Turkey. In 2021, he received his Ph.D. in Civilization Studies: political science from the Alliance of Civilizations Institute of Ibn Khaldun University, Turkey. His thesis is entitled “The Construction of a Theory of Civilization Through the Works of al Māwardī.” In 2006, he gained his BA degree in political science from al-Quds University in Jerusalem. In 2009 he received his first master’s degree in international studies from the Birzeit University, and in 2013 his second Master’s degree in Political Theory from the Goethe University Frankfurt am Main and the Technical University of Darmstadt, Germany. His academic publications appeared in the Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, Insight Turkey, and Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization. Besides his native Arabic language, he is fluent in German, English, and Turkish. His research interests are Ethics and Politics, Political Theory, Civilization Studies, Theory of Civilization, Islamic Thought, Classical Muslim thoughts, and Palestinian-Israeli conflict.