Tim Marshall is a contemporary author who gives great importance to the factor of geography in shaping the history of nations, their current status and future. The author has more than 25 years of experience as a traveling reporter for major media organizations such as the BBC and Sky News. He covered conflicts and wars in forty countries, writing reports on Libya, Afghanistan, Balkan countries, Lebanon, Syria, and others. This experience resulted in well-known and award-winning books such as “Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Tell You Everything You Need to Know About Global Politics”, “The Age of Walls: How Barriers Between Nations Are Changing Our World”, “Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of Flags.” He has an easy and fluid style of writing in dealing with complex geopolitical topics. In his book, “The Power of Geography: Ten Maps That Reveal the Future of Our World” (2021), Tim Marshall explores ten geographical states/regions that will shape global politics in a new era of great power rivalry: Australia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, Greece, Turkey, the African Sahel, Ethiopia, Spain, and the outer space.

“The Power of Geography: Ten Maps That Reveal the Future of Our World” is an extension of his famous book “Prisoners of Geography”, which focused on the major players (such as the United States, Russia, and China) and the major geopolitical blocs (such as the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, and Africa). Both books show how countries find themselves limited in their political and strategic choices by mountains, rivers, seas, and climate, making the physical geographic factor a key factor in determining what humanity can and cannot do.

Also, he argues in both books for the return of geopolitics in the twenty-first century and the continuation of geography as a force that explains the behavior of states, shaping them and influencing global politics despite the outcomes imposed by globalization that shrunk the effectiveness of the geography factor or eliminated it, as globalist liberals claim. Humans have the ability to choose, but this is never separate from the physical geographical context in which these choices take place. The story of any country starts from its geographical position in relation to its neighbors, shipping lanes, and natural resources.

“The Power of Geography” covers some of the events and conflicts that have come to the fore in the twenty-first century, with the potential to have far-reaching consequences in a multipolar world. This summary deals with the chapter on Australia, the island-continent that appears geographically isolated from the world but has an important geopolitical weight that will tip the balance of the most prominent coming competition in the twenty-first century between the United States and China.

The “Isolated” Continent: A Geographical Diagnosis:

At the beginning of this chapter, the author presents a geographical analysis of Australia that will later help readers understand the impact of this continent-country’s geographical nature on its strategic choices and its geostrategic status in the context of the great-power competition between the United States and China in the twenty-first century.

This huge island is located 11,500 km south-west from the United States, 8,000 km west from Africa across the Indian Ocean, and is separated from the Antarctic continent by 5,000 km in the south. The geopolitical meaning of this “island-continent” emerges only by looking to the north, where a group of Western-oriented democracies are located. Above them in the north, as he says, is located “the most powerful dictatorial country economically and militarily, China.” Australia in this sense is not just an island isolated from the world, but is a huge country located right in the middle of the Indo-Pacific region, the region that is host to the most powerful global economies in the twenty-first century.

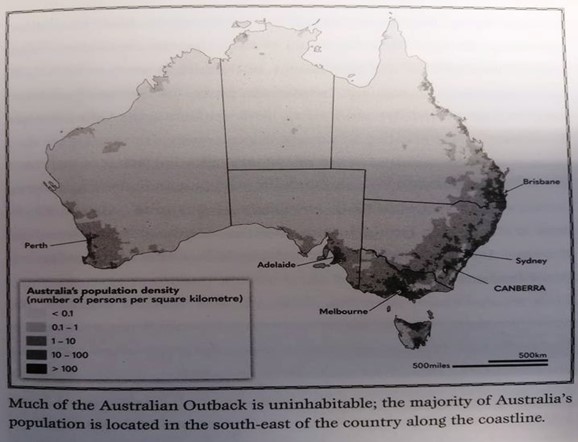

Australia is the sixth largest country in terms of surface (7.5 million sq km), the driving distance from Brisbane in the east to Perth in the west – to cross the country- is the same distance from London to Beirut via France, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Serbia, Bulgaria, Türkiye, and Syria. It is currently divided into six major states, the largest of which is Western Australia, which represents a third of the continent, and is larger than all Western European countries combined. Then comes Queensland, South Australia, New South Wales, Victoria and the island of Tasmania in the far south. Its main territories are the Northern and the Australian Capital territories. The country has about 25 million people (more than 80% are white, mainly British, and from Western Europe in general, in addition to immigrants from Asia and neighboring countries, with about 3.3% from the aboriginal population according to the 2016 census). Population density is located on the eastern fringes, especially the southeast, and the southwest around the city of Perth as shown on the map below. 50% of the population resides in Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane.

The country’s most challenging factors are land and climate. About 70% of Australia is uninhabited remote areas due to its rugged topography (dense forests, wide dry plains devoid of water, deserts, and mountains…). When the 2019/2020 fires broke out, a huge amount of livestock and plants perished as residents were unable to save them, with suffocating smog covering major populated cities for days, and the temperature in Sydney reached 48.9 °C. Residents feared the scarcity of water, which is an already fundamental problem in the country because of its topography. Most of Australia’s rivers are seasonal inflow, and there are only two large permanent flowing rivers, namely the Murray River and its tributaries, and the Darling River. Both located to the east closer to the south, they are navigable by smaller ships, but have limited access to sea entrances to enable cargo ships to transport goods inland. The Darling and Murray Basin region is Australia’s agricultural and food basket.

Coal is a major energy resource for the country, all states have coal mines, and its factories employ tens of thousands of people. But as the industrialized world turns to reduce carbon emissions and reduce pollution, this will have a profound impact on the country’s economy. The issue of energy access has been a major concern for Australia. Given the country’s geography and location, it is not possible to separate this issue from security issues.

How Geography Has Shaped Australia’s Strategic Choices Since World War II:

The author presents, in several pages, a summary of the history of this country’s founding, the migrations it received, and how it was founded and then gradually transformed into one of the most powerful liberal democracies since the 1960s. The story of Australia begins at the end of the eighteenth century when the British wanted to deport convicts and prisoners to the farthest reaches of the earth. After World War II, the country then turned into a close ally of the United States and the West with a geostrategic position in the Cold War and the following years.

Australia’s geographical location and its size are both strengths and weaknesses. They protect it from external invasion but also restrain its political development. Most of Australia’s strategic focus is on the north and east, with its eyes on the South China Sea as its first line of defense. To the east, its focus is on the islands of the South Pacific, such as Fuji and Vanuatu.

Australia has some geopolitical advantages, for example, it is difficult to invade (not impossible, but hard), as any invading force must began from sea. Because of the islands located east and north of Australia, the potential lines of attacks remain narrow. It is not easy to conquer the entire continent’s shores, and its valuable places will be closely guarded. For example, any enemy that places their forces in the Northern Territory will have 3,200 km to reach Sydney, leading to severe problems in supply chains.

In return, Australia needs a strong and huge naval fleet to secure itself, commercially link with the world and guarantee freedom of navigation through commercial sea lines and ensure its openness and security. In addition, the country remains easily exposed and subject to embargo, as most of its exports and imports pass through a series of narrow corridors located in the north, any one of which can be subject to closure in the event of conflict. These passes include the Straits of Malacca, Sunda, and Lombok. The Malacca Strait is the shortest route between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, through which 80,000 ships alone pass annually, carrying one-third of the world’s trade goods, including 80% of the oil heading towards Northeast Asia, and any other alternative routes are very expensive and take longer to transport. Any successful blockade scenario on Australia would quickly put it into an energy crisis, with only two months of oil supplies in its strategic reserves.

Australia has built its defense strategy in part taking into account such a scenario, as it has warships and submarines that can protect energy convoys and aircraft with the ability to conduct long-range maritime patrols. Also, it has six military bases for its Air Force located north of the 26th parallel that divides the country in two, three full of teams and equipment, and the other three on standby in case of emergency.

However, given the country’s size, population, and modest wealth, Australia cannot operate freely and it not capable of protecting all the seas near its shores. Conducting maritime patrols in the seas near Australia is indeed a challenge. To counter any frightening scenario and invest more heavily in its navy, Australia is focusing on diplomacy and carefully choosing its allies. It has always cared about the world’s most dominant naval power. In the past, Great Britain was its most important ally, and then it has been gradually replaced by the United States since World War II as the country’s primary political, military, and strategic ally.

The author talks about the history of Australia-US strategic links since the Pearl Harbor attacks in 1943 and the landing of American forces in northern Australia. From that moment on, Australia became a critical geostrategic region for the United States. Australian forces have been involved in US wars, sending soldiers to battlefields such as the Korean War (1950-1953), the Vietnam War (1955-1975), and even the two Iraq wars in 1991 and 2003. In return, the US provides its nuclear umbrella to Australia and protects freedom of navigation in the seas and vital straits. In the Darwin area in the far north of the country, Washington has kept a primary military base since World War II, reinforced by 2,500 Marines, who keeps a watchful eye on China and signal to the Australians that they are ready to defend the country against any external threat.

Canberra’s Geopolitical Dilemma and the US-China Rivalry in the Asia-Pacific Region:

With the rapid rise of China since the beginning of the new century, Australia finds itself in a real dilemma, especially since US strategy towards China is still not entirely clear. US diplomatic and military officials have maintained that the alliance with Australia is rock-solid, but the US former President Donald Trump rattled Australia with his constant hints of his admiration for Asian dictators such as the North Korean leader at the expense of America’s well-established democratic allies there. However, the tone of American rhetoric returned to the status quo with Biden’s arrival in the White House.

China’s demands in the South China Sea pose a threat to Australia, especially with Chinese projects and their commercial or military movements there, such as fishing, building artificial islands, maritime monitoring patrols, and others. Australia realizes that by the middle of the twenty-first century, US defense spending will no longer outperform its Chinese counterpart. If the Soviet Union collapsed due to its economic weakness and inability to match the United States militarily, the matter with China is completely different, as the economic rise of China continues and experts expect Beijing to overtake Washington in terms of GDP by mid-century, if not sooner. Therefore, America’s choices on these issues will affect Australia’s stance regarding China.

The author believes that China and Australia will be relatively close to each other due to two factors. First, the geographical distance between Beijing and Canberra (Contrary to how it appears on most maps, the distance between Beijing and Warsaw is the same as the distance between Beijing and Canberra). Second, the intertwining of economic-commercial interests and the movement of individuals between the two countries. Here, the author presents some figures. For instance, China is Australia’s largest trading partner by a long run. In recent years, about 1.4 million Chinese annually visit Australia for vacation, and Chinese students represent more than 30% of foreign students studying in Australia. China buys almost a third of Australia’s agricultural production and is also a major market for Australia’s iron ore, gas, coal, and gold resources.

However, the author believes that the Chinese claims in the South China Sea complicate Australian-Chinese relations, as China claims more than 80% of the South China Sea as its geographical and historical right. It is installing radar and missile batteries on some of the prominent rocks far away from its shores, ignoring the historical and geographical demands of some of its neighbors such as the Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Brunei. Therefore, Australia today fears that China will push forward to expand this region in its favor from Japan in the north to the Australian borders in the south then push the US out of the region in a case of war, especially since the Australians still retain a vivid memory of the Japanese invasion that reached their borders. One scenario for Canberra’s response is the rapid mobilization of Australian military forces to deter the Chinese. However, Australian geography poses a challenge to the positioning of these forces. Placing them in the north will make them vulnerable to the enemy while placing them in the south will make the process of moving them take longer.

The author argues that Australia does not have the ability to prevent China from dominating the South China Sea, but it is able to ensure that Beijing has limited influence in the South Pacific, for example, Canberra is the largest provider of aid in the region. Aid is a way to make the islands there under its influence far from China. Beijing realizes this game and is moving to gain some influence in the South Pacific. The author mentions an accident that happened to an Australian plane in April 2020, which was loaded with medical aid in the midst of the Covid-19 crisis, heading to the island of Vanuatu, as it approached the narrow runway of the island’s airport, it was glimpsed by a Chinese plane that arrived earlier to provide medical equipment against Covid-19. The Australian plane returned back without landing. Regardless of the reason for return, the incident was a strong signal from the Chinese that they have now advanced and were on the ground.

In addition to other goals on the ground, China is also seeking to win the support of those island-states in the South Pacific regarding the Taiwan issue at the United Nations. For example, in 2019 it succeeded in making the Kiribati and Solomon Islands sever ties with Taiwan and establish diplomatic relations with China, despite the intense activity of American and Australian lobbies there.

Australia has been working for a while to strengthen its ties with the South Pacific islands to restrain Chinese influence. It has funded the main military base in the Fiji Islands, signed a bilateral security agreement with Vanuatu, and donated 21 new military boats for maritime surveillance to many of the islands there. Moreover, aid budget is earmarked for the construction of a high-speed underwater communication network called the Coral Sea Cable System to connect Australia with the Solomon and Papua New Guinea Islands. Despite all these Australian measures, China has achieved success there, especially in the islands of Fiji, Cook, and Tonga.

China is economically, militarily, and technologically superior to Australia. Also, its cyber capabilities allow it greater influence and movement in Australia’s neighborhood and makes Australia itself a besieged country. Canberra has been subjected to some kind of Chinese “alerts and sanctions” in the midst of some periodic diplomatic tensions between the two countries, such as in mid-2019, when Australian Prime Minister Morrison alluded to China’s involvement in the ongoing cyberattacks on the Australian government and sensitive sectors of the country’s infrastructure such as health and education. Therefore, Australia’s mishandling of China will leave it caught in the middle of a dangerous cold war in the Indo-Pacific and surrounded by Chinese military bases in its backyard. The Covid-19 crisis has accelerated and amplified the fear of China’s rise among the region’s countries. At a time when Japan, India, Taiwan, Malaysia, Australia, and other countries were preoccupied with their battle against the pandemic, China was making provocative moves, including moving its aircraft carriers in a full circle around Taiwan.

Therefore, Canberra finds security only in its excellent historical relations with Washington. The two countries enjoy a high level of security and military relations. Australia, for example, is considered one of the “Five Eyes” countries (alongside the US, the UK, Canada, and New Zealand), the largest effective intelligence-gathering network in the world. It also hosts on its territory the Pine Gap military base, which is the most important base for collecting American intelligence information in the world, with many military and security functions covering the entire region, all the way to Afghanistan. The author concludes this chapter by affirming the urgent need for intensive cooperation between Australia and the countries of the region on the one hand, and between Canberra and Washington on the other hand, to secure shipping lines and trade, the safety of supply chains, and the security of the straits as well, as closing of the straits, for instance, will stifle the economies of these countries and put them at stake.

All the region’s countries agree on this issue. Doing so requires stopping China, repelling its demands, and refuting its lies about its rights and sovereignty over the South China Sea. Some of the key countries there share membership in “the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue” (the Quad), which includes Australia, Japan, India, and the United States. This institution is not considered an alliance but is closer to a strategic framework for coordination between the naval power of these four countries. The institution aims to achieve cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region, secure shipping lines, and supply resources there, and most importantly, defeat Chinese influence. There are talks today of expanding this institution (Quad Plus) to include New Zealand, South Korea, and Vietnam, despite the extreme caution shown by the latter two countries due to their geographical proximity to China.

Thus, the author concludes by clarifying the critical geopolitical situation that Australia suffers from mainly because of its geography, which makes it face difficult strategic choices and pushes it to balance very carefully in its region. Any wrong move might lead to serious and sustainable consequences in a region that is today considered the most economically important region in the world.

He is a leading authority on foreign affairs with more than thirty years of reporting experience. He was diplomatic editor at Sky News and before that worked for the BBC and LBC/IRN radio. He has reported from forty countries and covered conflicts in Croatia, Bosnia, Macedonia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and the occupied Palestinian territories. He is the author of Prisoners of Geography, The Age of Walls, A Flag Worth Dying For, The Power of Geography, and The Future of Geography.

He is Research Fellow at the Center for Islam and Global Affairs (CIGA), affiliated with Istanbul Zaim University –Türkiye since December 2019. His main fields of interest are Geopolitics, IR theory, Great Power Politics and International System, Geopolitics of North Africa, Eurasia, and the South China Sea, Turkish Foreign Policy, and Algerian Foreign Policy. He is the author of many books, studies, translations, and academic summaries published in Arabic and English. His books include: “The Struggle for Free Will: Turkish Foreign Policy in a Changing International System (1923-2017)” (2024), “The Liberal International Order: Rise or Fall? John Ikenberry VS John Mearsheimer” (2021), “The Prospects for Democratic Transition in Russia, a Critical Study for Structures and Challenges”, (2015).